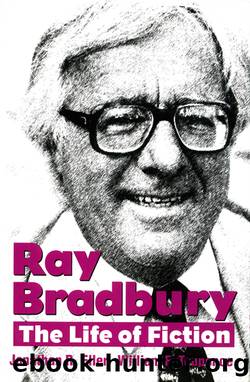

Ray Bradbury by Eller Jonathan R.;Touponce William F.;Nolan William F.; & William F. Touponce

Author:Eller, Jonathan R.;Touponce, William F.;Nolan, William F.; & William F. Touponce

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The Kent State University Press

This carnivalâcompared to a movie screen that stages desireâsets itself up in the darkest hours of the night. Why does Bradbury reverse the traditional associations belonging to this literary chronotope? We have to remember that he is writing after Freud, in a culture that has internalized the Gothic to an extraordinary degree. Tzvetan Todorov has indicated, in a statement that has provoked some controversy, that there is no literature of the fantastic in the twentieth century because psychoanalysis has taken over its themes.51 This assertion has been largely confirmed, though inadvertently, by recent studies of the American Gothic, such as Mark Edmundsonâs Nightmare on Main Street. Edmundson does not consider the possibility, however, that fantastic literature could take revenge on psychoanalysis for this encroachment by making psychoanalysts figures of fun (or even serial killers themselves; the stories of Clive Barker or films like Brian di Palmaâs Dressed to Kill manifest this widespread tendency) in stories that discredit their authority or show their theories to be fictions. That is the cultural processâcarnivalizationâthat is happening in Something Wicked.

Bradbury carnivalizes each genre in which he works. Here it is a question of the horror, or dark fantasy, genre whose themes have been dominated by Freud and based on Oedipal and familial fears. But in Something Wicked Bradburyâs strategy is less direct than in his short stories and poems. There is no psychoanalyst overtly represented in the literal story. But the carnival itself, because it functions by feeding off the desires of people for lost objects, their guilt and sense of debt, and especially their narcissism, is similar to the psychoanalytic machine as parodied in some recent Nietzschean-inspired anti-Freudian polemics: âthe psychoanalyst parks his circus in the dumbfounded unconscious, a real P. T. Barnum in the fields.â52

Another interpretative issue to be dealt with, then, is the fact that Something Wicked speaks to us in the language of images derived from carnival that are indirect and often have a metaphorical and even allegorical significance.53 But carnival should not be translated into a language of abstract concepts. Instead, one must investigate how carnival laughter, symbols, and its sense of change can be figured by literature and, through understanding them, again regain some sense of participation in it, the authentic use of the carnival being identified, according to Bakhtin, with our sense of carnival having only just been transformed into literature. Everything in Bradburyâs text, its discourse and themes, strives to achieve this effect.

Here we want to mention that Bradbury conducts his critique of the Freudian view of man (as driven by unconscious desires he can never fulfill and by self-punishment for having those very desires) by the technique of carnivalizing the carnival and by masking his main character as a fool who, because of his âoutsidedness,â is able to resist its temptations. Fearful things such as Mr. Dark must also be masked in Bradburyâs aesthetic. This is not to suggest, however, that Something Wicked is purely an allegory. Although his name suggests some such function, Mr. Dark does not represent the abstract allegorical idea of the evil father.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Happiness by Di Leo Jeffrey R.;(137)

Kubrick Red : A Memoir by Simon Roy; Jacob Homel(100)

The History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic â Volume 3 by William Hickling Prescott(99)

Ray Bradbury by Eller Jonathan R.;Touponce William F.;Nolan William F.; & William F. Touponce(95)

Forms of List-Making: Epistemic, Literary, and Visual Enumeration by Roman Alexander Barton; Julia Böckling; Sarah Link; Anne Rüggemeier(92)

N by E by Rockwell Kent(81)

Bitter Carnival by Michael Andr Bernstein;(77)

Bohemians by David Weir(75)

Walter Scott at 250: Looking Forward by Caroline McCracken-Flesher; Matthew Wickman(71)

The Residues, Part One Collected Writings 1990-2020 by Stephen Barber(68)

Bookclub-in-a-Box Discusses Small Island, by Andrea Levy by Marilyn Herbert(67)

Milton's Ovidian Eve by Mandy Green;(66)

My Love Must Wait by Ernestine Hill(65)

Sisters of Tomorrow by Sisters of Tomorrow- The First Women of Science Fiction (epub)(65)

One Thousand Questions in California Agriculture Answered by Edward J. (Edward James) Wickson(65)

The Collected Novels by Khushwant Singh(64)

The Perfect Tribute by Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews(62)

The Stone Lion and Other Chinese Detective Stories by Yin-Lien C. Chin(62)

A Study Guide for Psychologists and Their Theories for Students: Albert Bandura by Gale Cengage Learning(57)